Useless #1: Fermín Jiménez Landa

56x45x25

29.10.2016 – 15.11.2016

*To schedule an appointment write to 56x45x25(at)vistaoral.net.

Fermín Jiménez Landa. (Pamplona,1979)

Fermín Jiménez Landa, works in performance, public intervention, video, installation or drawing. He uses equivalence, inversion and substitution processes that make us see reality from an equidistant point between absurdity and wisdom, charming and iconoclastic, empirical and unverifiable.

He has crossed Spain through a perfect line of swimming pools, broken the deadlock of the two highest towers of Barcelona with a plastic tree, conquered a Greek islet with a national anthem, travelled without touching doors, spoken with Felix Rodriguez de La Fuente about his fake documentaries, ordered confetti by color and seeded giant sequoias in the streets. +info

Three photos and a sentence, this is how our collaboration with Fermín started.

56x45x25 takes as a starting point a metric system, that is a cultural setting where the paradox and utopia of the translation becomes very obvious. Language configures reality and also maximizes the imaginaries. This project is based on one of these imaginaries. In Spain it is believed that Americans can get a car the same way they buy the newspaper. The ease and the link between the average American using a vehicle has been fuelled by countless series and films that dominate the main television channels in Europe. In them, not only the dumbest low to medium class teenagers get their first car when they still have no right to vote; but it is also implied that you can drive a car torn apart and that there is no such thing as a complete car inspection. At this point it should also be clarified that until a month ago none of us had a driving license. Since then the resident in LA has it.

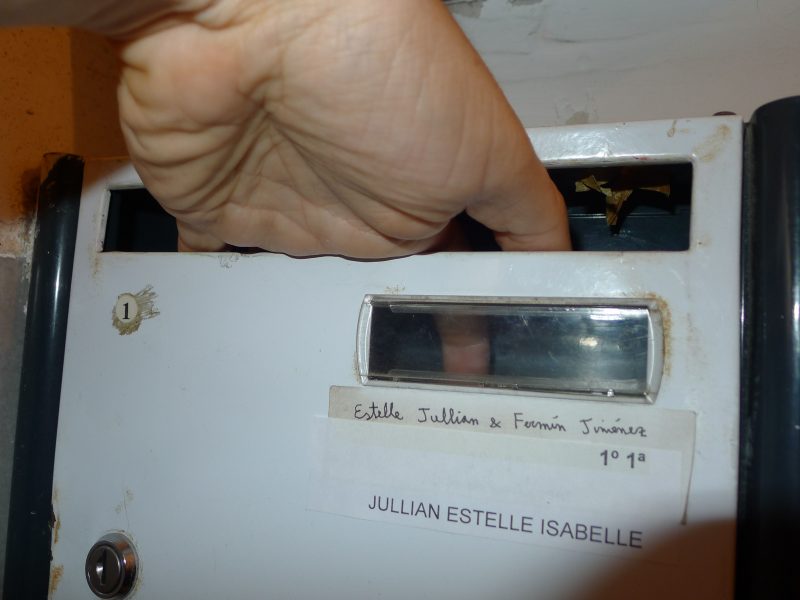

The thought that the first 56x45x25 project was to put a car in an empty garage excited us, mainly because of the waste of time involved converting a garage into an exhibition space to end up putting a car in it. Fermín suggested to send us his mailbox key, hence the photo of his hand, and encourages the visitor of the exhibition to scratch the car, a reified aggressiveness that can be read in multiple layers.

Having said that, all that was left was the silliness of getting a car, which would be an investment of what…say… $250? Manageable, despite our precariousness.

The first thing we did was to ask people in LA. They had two suggestions: scrapyards and Craigslist. We went ahead and visited the scrapyards in the city. We thought it would be easy: borrow a car from a scrapyard for three weeks, use it for our project and take it back afterwards, maybe paying only a bunch of dollars. If the car was going to be destroyed anyway it should be something easy. But, after having various conversations, we realised that that option wasn’t easy at all. The scrapyard sells cars by parts, and scratched parts have no value. Furthermore, the cars have insurance that is in the scrapyard owner’s name, who wasn’t really up for lending a car to strangers for three weeks doing something that he couldn’t understand. We got rid of that option.

So, we started our search on Craigslist. We googled about cars, those objects that we have no clue about, and that we refer to according to its shape and colour. We learned something. At least we understood what does a ‘savage’ or a ‘clean’ title mean . So we took into consideration two options:

a) Buy a car that doesn’t work at a very cheap price, use it for the project and take it to the scrapyard afterwards.

b) Buy a car that works at a very cheap price, use it for the project and drive it afterwards, scratches included. The option that we felt would give greater significance to the project. Questioning certain established values, such as discipline or fear. The act of violence against us without a simulated scenario.

Estos detalles nos fascinaron en CraigsList. Anuncios de coches en los que se tapa la matrícula

After hours of searching on Craigslist we found a few cars that matched our two options. We visited the sellers. We tried out the cars. We were about to buy one, a white Saab convertible. It had had a major accident a few months ago but had been repaired. When we were about to buy it, we had a mishap with the seller, who was feeling uncomfortable with our insistent questions about the condition of the car, he raised the tone of the conversation reaching the limit of wanting to «fix it in the street» with a fairly violent tone. Given the clear signs of unbalance from our interlocutor and how easy it would have been for him to break our face, we decided not to buy it and we returned home without a car.

These mishaps didn’t discouraged us. We found another one that we really liked, an old, maroon T-Top where the bodywork was in good condition, something essential to be able to carry out the collective scratching during the exhibition. We drove for two hours to get to Moreno Valley, the place where the seller had the car. We met up with him. He took us for a ride. After a lot of insisting, he let us try it. It didn’t work very well at all but we negotiated a price way under the initial one, therefore we got excited and decided to buy it. The transaction was in cash. We took the car to go home. 45 seconds after we started driving, we got pulled over by a policeman. Apparently the registration plate had been falsified with a small sticker. We explained him that we had literally just bought it. We showed him the paperwork and also a photo that we took of the seller’s ID card. The policeman smirked. The seller was well-known in the area. Apparently he had got out of jail not long ago. He had had problems with selling second-hand cars. He had cheated us. The next day we went to the DMV, the Department of Motor Vehicles, to find out the condition of the car and put it under our name. It turned out that the car had some pending payments, which totalled $500. We also went to see a mechanic. To fix up the car and make it roadworthy would cost us $2000. Make it pass the emissions test to be able to drive it would be $250. We decided not to fix it, nor to put it under our name. We’ll use it only for the project. Then we’ll take it to a scrapyard. We won’t drive it. We won’t hide the fact that it was from that moment that the discouragement started and we began questioning the viability of the project.

The incentive was Fermín. His work is linked to processes that seem to have an imprecise end; anecdotal beginnings in the path are incorporated as accidents that become parts of the work itself. Curiosity as a starting point from where failure is mentioned as a possibility, and never get to know fully whether it is a scam or not. We had become an active member of one of the many questions that go through Fermín’s mind. There was no going back, nor forward. This irrelevant and totally useless act was already the project, we were aware of it as we spoke with Fermin by Skype, from three different parts of the world: Los Angeles, Barcelona and Finland, to be more precise, Suomenlinna island. Meetings that were infested with technical errors that were foolish in their own way but at the same time very rewarding.

We continued from where we left off. Fermín would send us his mailbox key from Helsinki by FedEx. FedEx turned out to be just as absurd. If it didn’t have a function, it could be considered to be a poetic action. As the account was in our name, the suggested shipping method by the courier company was to send an empty envelope from LA to the offices where Fermin was doing his artist residency, then he would introduce the key into the envelope with the appropriate labels and sent it back to us. This whole game of tempos would make it impossible for the key to arrive on time.

– The other issue is that tomorrow I’m going to Spain, I don’t think things will change whether we send it from here or there.

–Fermín, shall we see each other at Cinco?

Maybe three and a half hours in a train to get to a bar is a small issue for any resident of LA, but not for any average Spanish. Finally, on October 20th, at an inexact time in the morning, Fermín handed over the key for his mail box during a meeting at Bar Cinco in Valencia, the most similar thing to an office that we have had to work together.

The key arrived in LA on October 23rd despite the uncertainty that created the complaints of the FedEx messenger for not having enough copies of delivery notes and a computer system that did not indicate that the doorbell was not working properly.

Everything seemed to be on track, we were focusing on working on the publication’s content and the insignificant details that continue to be critical in setting up an exhibition. Then, when the project was only missing small technical details, the car disappeared. It had been towed.

Let’s sum up the cluster of problems that we knew the car had: false registration, acquired debt, fifty previous owners. Obviously it was not in our name because of all of the above. Concatenated events as if it were all a massive simulation coming from Fermin and we were the active subjects infiltrated in this continuous sabotage.

It was raining in California, the kind of weather that goes well with psychodramas, and in cities like Los Angeles, the weather that causes a system crash at all the DMW offices LA. After two days of painful wait, paying fines and debts incurred by others, we could resume the project. And like that, part of the game ends here, something we have done because we felt like it; it is not profitable, it is unselfish. Something that happens in this space where the poetic and the philosophical can exist. An interruption in our lives that gives way to the absurdity and the playfulness, through the pursuit of something that we have no interest in owning. A challenge to the ‘why’ and the ‘what for’ that takes place in a space through a key, a photo and a car.

The photograph functions as a spatio-temporal connection with a flat in Valencia, with another series of consequential related events.

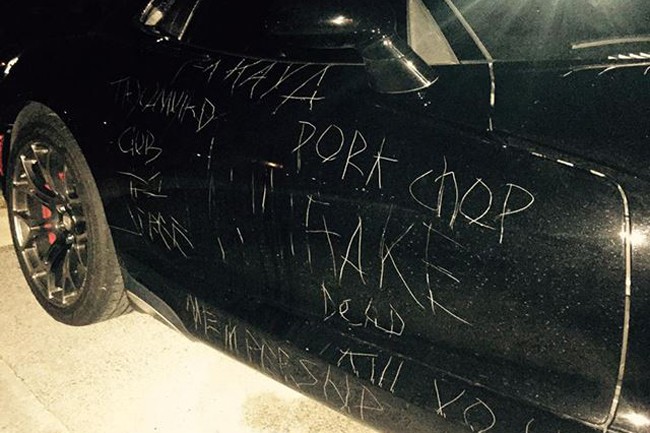

In the car, the first signs of vandalism, measured, orderly and almost strenuous. Mechanical scratches that reminds us of an expressionist act more than a macarrada (loutish thing).

Routine and permissiveness as a clear source of depotentialization of the aggression.

A surface that you run a key over, to waste time, which is useless.

An invitation from Fermín, to scratch the car.